Universal artificial blood: Where science stands today

By: Dr. Avi Verma

For decades, the idea of artificial blood, a safe, universally compatible substitute for donated human blood, has been a long-sought goal in medicine. Such a product could help avert global shortages, eliminate the need for blood-type matching, and save countless lives in emergencies ranging from trauma care to battlefield injuries. Today, science is closer than ever before to realizing this vision, with significant progress in Japan, promising research in the United States, and emerging discussions in India.

Japan at the forefront as universal artificial blood enters human trials

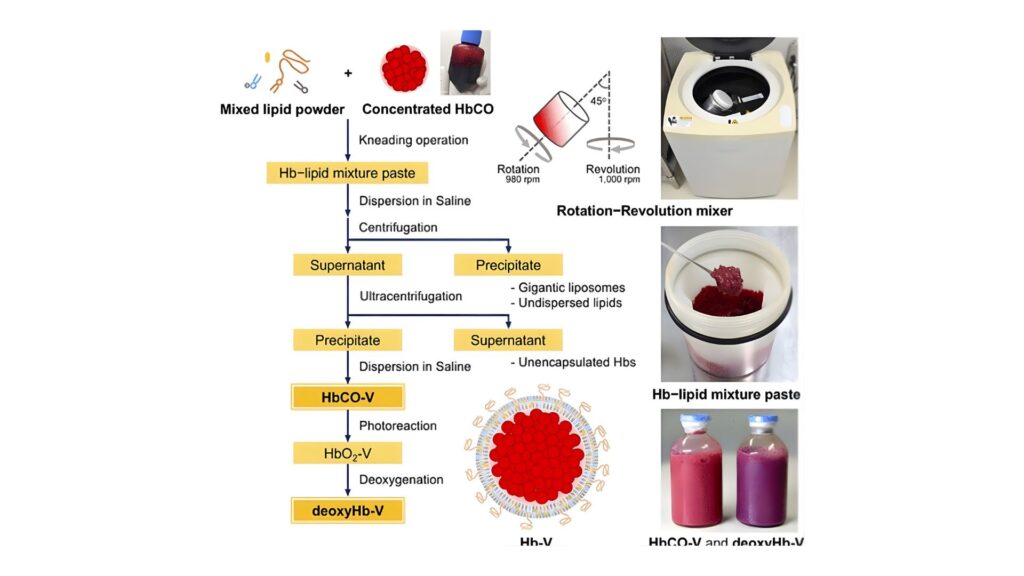

Japan currently leads the world in artificial blood research, with scientists conducting the first modern human clinical trials of a truly universal blood substitute. This work is centered at Nara Medical University, where a team led by Professor Hiromi Sakai has developed an innovative product based on hemoglobin vesicles, tiny microscopic particles engineered to transport oxygen without the complex components of whole red blood cells.

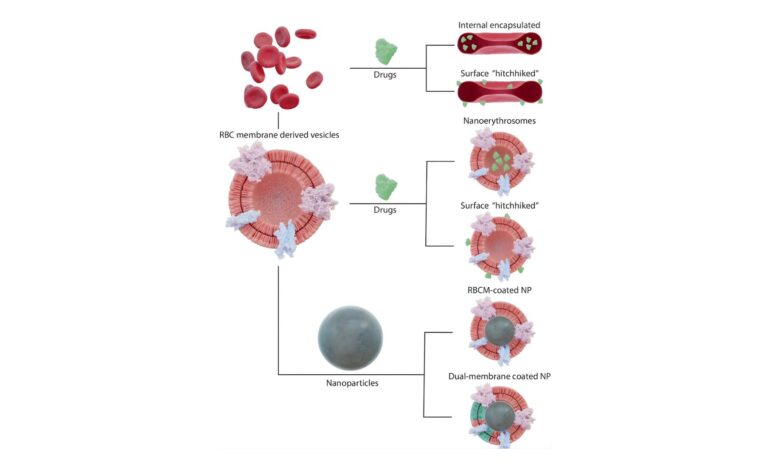

Hemoglobin, the protein that carries oxygen in normal red blood cells, is purified and encapsulated inside a lipid membrane that mimics the cell’s structure. This design has several important advantages:

Universal compatibility: Hemoglobin vesicles lack ABO and Rh blood group antigens, meaning they can be transfused into any patient without blood-type matching.

Oxygen delivery: The vesicles carry oxygen through the bloodstream in a manner similar to natural red cells.

Extended storage: Unlike donated blood, which must be refrigerated and used within about six weeks, these artificial cells may be stored for up to two years at room temperature or longer under refrigeration, potentially transforming logistics in emergency settings.

Reduced infection risk: Removing cellular components lowers the risk of immune reactions and infectious disease transmission.

In March 2025, Japan began administering the hemoglobin vesicle product to healthy adult volunteers in doses ranging from 100 to 400 milliliters as part of a Phase Ib clinical trial designed to evaluate safety, tolerability, and how the artificial cells behave in the body. Early results have been encouraging, showing that the vesicles remain in circulation and do not elicit major adverse effects at these doses.

If the trials continue to demonstrate safety and acceptable physiological performance, Japanese researchers estimate that clinical use, especially in emergency medicine, disaster response, and military applications, could realistically begin by around 2030.

United States: Decades of research with cautionary lessons

The United States has a long history in artificial blood research, though progress has been slower and more cautious than in Japan. During the 1990s and early 2000s, various hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers were tested as potential blood substitutes. Products such as PolyHeme and HBOC-201 demonstrated the ability to transport oxygen but revealed significant drawbacks in human trials, including vasoconstriction, increased cardiovascular risk, and inflammatory responses.

These findings prevented regulatory approval and led to the discontinuation of most early programs. The Food and Drug Administration has since adopted a cautious stance, supporting research aimed at understanding and reducing toxicity risks.

Newer efforts such as ErythroMer, developed with support from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Defense, seek to overcome earlier limitations. ErythroMer is a polymer-coated hemoglobin powder that can be freeze-dried, stored, and rapidly reconstituted, with promising animal study results showing improved oxygen delivery and lower toxicity. However, as of early 2026, no artificial blood product has entered advanced human trials or gained approval in the United States.

India focuses on strengthening traditional supply systems

India currently does not have active clinical trials involving artificial or universal blood substitutes. Earlier exploratory research did not develop into sustained programs due to cost constraints, regulatory complexity, and unresolved safety concerns.

India’s strategy remains focused on expanding voluntary blood donation, strengthening blood bank infrastructure, and improving screening and storage systems to meet high demand from trauma care, maternal health, and surgery. Artificial blood remains a topic of scientific interest rather than active clinical development.

Why artificial blood has been so challenging

Artificial blood research faces persistent hurdles, including toxicity of free hemoglobin outside red blood cells, ensuring safe oxygen delivery across varied conditions, and avoiding immune reactions. The hemoglobin vesicle approach pursued in Japan is promising because it closely mimics natural red cells, but larger trials are essential before widespread use.

A future still unwritten but filled with hope

Japan’s trials suggest that a safe, type-neutral, shelf-stable blood substitute may be within reach, potentially transforming emergency care by the end of this decade. Research in the United States continues to refine next-generation approaches, while India focuses on optimizing existing systems. As challenges are addressed, a once fictional idea is becoming a tangible scientific reality with the potential to save millions of lives.

Disclaimer

The information presented in this article is for educational and informational purposes only. Artificial or universal blood products discussed here are experimental and are not approved for routine clinical use in most countries. Ongoing research and clinical trials are required to establish safety, effectiveness, and long-term outcomes. This article does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment recommendations. Readers should consult qualified healthcare professionals for personal medical guidance and rely on approved medical practices and regulatory authorities for clinical decisions.