‘Vote for.. or to vote at all’: Iran Presidential run-off presents stark choices beyond reformist vs hardliner

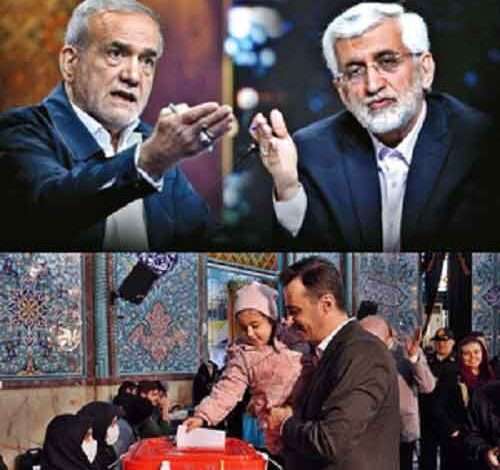

New Delhi, July 4 – He may have finished last in Iran’s Presidential race but cleric Mostafa Pourmohammadi made waves as the deemed conservative candidate not only displayed a rather progressive view but identified the underlying issue the regime is grappling with – and not very successfully – as reformist Masoud Pezeshkian and ultra-conservative Saeed Jalili clash in the run-off on Friday.

Pourmohammadi, in a public message after his first-round exit, hailed those who had cast their ballot but also expressed “respect” to all those who “did not believe us and did not come”.

Turnout in the polls was just 40 per cent – the lowest since 1979.

“Your presence and absence are full of messages that I hope will be heard. Your message is clear and unambiguous,” the cleric said on social media.

As both Pezeshkian and Jalili wrapped up their television debates on Monday and Tuesday in which they presented their courses of action and clashed vigorously on approaches and mindsets on social, economic and diplomatic matters, the overriding issue in Friday’s elections is not just whether the reformist or the hardliner will prevail.

It actually is whether this question even concerns the great mass of the (absent) voters.

In more general terms, will the 60 per cent, who stayed away from polling booths on last Friday, shed their apathy to their participation in elections – restricted or imperfect as they may be – and keep faith in the exercise as a means of political and social change?

Turnout in elections – both presidential and parliamentary – has long been deemed as a sign of legitimacy of the Iranian system. However, these hopes have been belied in the present snap elections, as well as the parliamentary elections earlier this year (41 per cent) and the previous presidential elections (2021) – won by Ebrahim Raisi – at 48.8 per cent.

An impassioned appeal by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei before the June 28 elections seeking a “maximum” voter turnout as a message to the country’s “enemies”, seemed to have failed to sway the voters. It is to be seen what effect his fresh appeal ahead of the run-off will have – and the establishment will have to face up to the legacy issue sooner or later.

The turnout figured prominently in the debates between Pezeshkian and Jalili.

While Jalili called for examining why there is a “decrease in people’s participation” in elections”, Pezeshkian was more strident, terming it “unacceptable that 60 per cent of the people did not come to the polls”.

The reformist candidate also linked it to wider social and political issues like the internet curbs and the hijab issue, saying it also is due to women or some ethnic groups “that are not engaged by us”.

“When we ignore people’s rights and do not want to listen to their voices, expecting them to come to the polls is not a reasonable expectation. When 60 per cent of the people do not come to vote, we should feel that there is something wrong. There is a shortcoming,” he asserted, as per transcripts of the debates on Iranian media.

The statements by Pezeshkian – who is promising looser social curbs and negotiations to relieve sanctions pressure – were also addressed to the large section of the disillusioned reform-seeking yet non-voting electorate as he faces a clear loss if they again sit at home on Friday.

In the first round on June 28, Pezeshkian got 10.41 million votes, while Jalili was not far behind with 9.47 million, out of the 24.5 million votes cast, or just about 40 per cent of the 61 million-odd electorate.

Prepoll favourite – Majles Speaker Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf was the distant third with 3.38 million votes, while Pourmohammadi got 206,397 votes only.

The other two allowed candidates – Tehran Mayor Alireza Zakani and Vice President Amir-Hossein Ghazizadeh Hashemi – both conservatives – had quit days before Friday’s election.

As the election headed into a run-off as neither Pezeshkian nor Jalili secured the victory margin of 50 per cent plus one, Qalibaf, Zakani, and Hashemi appealed to their supporters to back Jalili. Pourmohammadi did not explicitly endorse anyone but his indirect attack on Jalili for attracting wider sanctions by blocking FATF recommendations is telling.

While the combined vote count of the conservative camp seems enough to propel Jalili to victory, there is a caveat.

As Pourmohammadi shows, despite appearances and (chiefly Western) perceptions, Iranian politics is not just two opposing distinct and united reformist or conservative camps, but a more fluid system due to many different sub-groups with their own agendas and aspirations. There is an overlap in policy too, whether of the conservative hardliners or the progressive reformists.

But political participation, or rather, the lack of it, remains an abiding challenge and it remains to be seen if Pourmohammadi’s hopes are realised.